By Caroline Newton

In the interstices of urban landscapes around the globe, there lies a ubiquitous yet often overlooked form of expression that occasionally captures the attention of passers-by.

These ephemeral markings, ranging from hastily adhered stickers, the so-called ‘slaps’ to inscriptions on walls,have fascinated me for the longest time.

The discourse on street art and its associated culture is extensive, encompassing various categorisations and assessments. Many scholars have engaged in discussions surrounding street art (e.g. Christensen & Thor, 2017; Dabène, 2020; McAuliffe & Iveson, 2011; Ross, 2016; Young, 2013, 2016) and the legal and moral debates regarding the dichotomy between art and vandalism have often dominated public forums.

Some studies have probed into the role of street art in political contestation and its relation to democratic principles in particular contexts. However, these discussions often veer towards the more visible and elaborateforms of street art, leaving the less ostentatious expressions comparatively under-examined. The work of Olivier Dabène (2020) in his book ‘Street Art and Democracy in Latin America’ meticulously examines street art’s role in fostering democracy across five Latin American cities, and commendably, Dabène doesn’t limit street art to just large pieces but includes a spectrum of interventions such as political messages, tags, graffiti, and an array of street art techniques like murals, stencils, posters, stickers, and collages, thereby offering an inclusive and diverse perspective on how these varying forms of street expressions can cultivate civic engagement, encourage public debates, and hold authorities accountable, while also shedding light on the complexities of public space governance.

Indeed, to me, these small, unassuming artefacts – the stickers, the words on walls, the paste-ups – often carry with them a potent essence of contestation. They can be seen as micro-manifestations of dissent, subtly critiquing dominant political discourses, challenging prevailing injustices, and, in their own unobtrusive way, agitating for change.

In this post, I aim to avoid discussing the commonly trodden path of debates over artistic merits or legal implications of street art. Instead, I plan to explore, in a very light manner, how these minor yet deeply significant articulations contribute to the broader socio-political landscape. How might they signify dissent and act as catalysts for fostering solidarity and collective action?

I will illustrate these musings with reflections upon examples of ‘‘Imprints of Contestation’’ that have struck a chord with me over the years. Through this, I hope to introduce you to these small but powerful signs you can find around our cities.

Why ‘‘Imprints of Contestation’’?

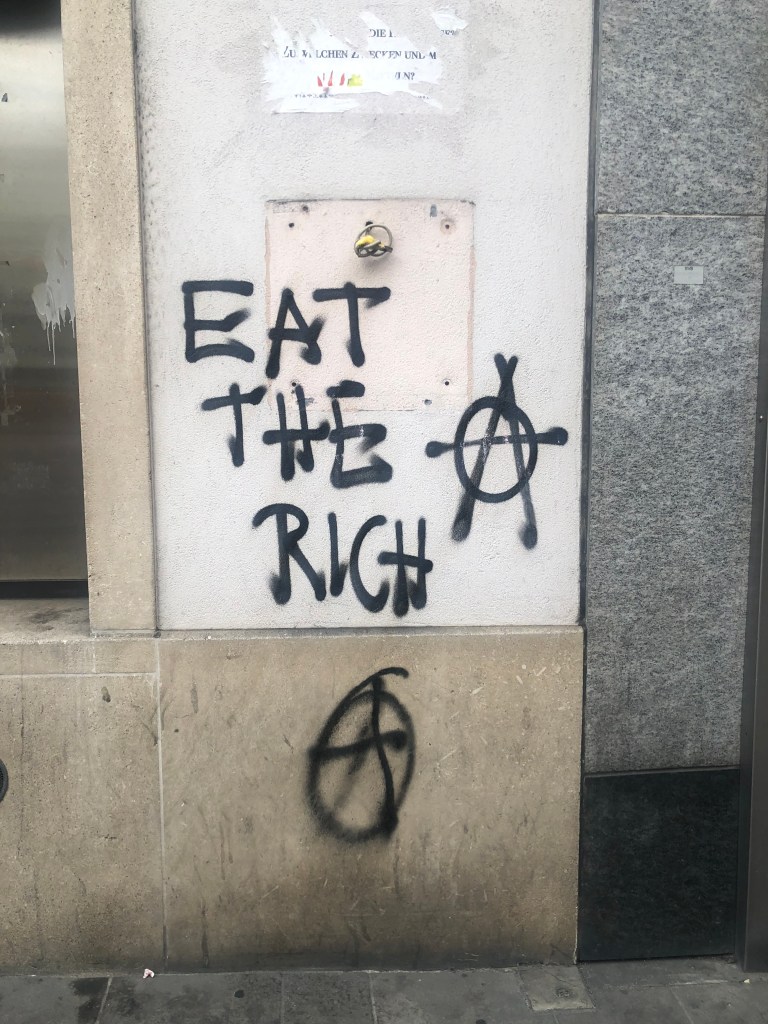

At its core, for me, this term refers to the small visual interventions scattered across urban spaces. As said above, think of the rogue sticker wedged onto a lamppost, the delicate stencil hidden on a street corner, or the scribbled words that seemingly challenge the world. These imprints are often inconspicuous, but they unmistakably convey defiance to me. Defiance against touristification, as illustrated by the picture from Venice, or defiance against animal cruelty, illustrated by the stencil art from Szczecin, Poland. But most of all, defiance against our neo-liberal system and capitalist drivers, as the source of most of the injustices we experience today. The clear message from Basel speaks for itself.

The often humorous or poignant approach to challenging dominant narratives and power structures makes these interventions stand apart. They are not mere decorations; they are declarations. They question social norms, highlight grievances, and sometimes offer alternative viewpoints or solutions. By doing so, they nudge the passers-by to question and to think.

They signify the diversity and complexity of the urban space’s voices and opinions. Though small in size, these visual expressions often bear important messages.

To me, these ‘Imprints of Contestation’ serve as windows into the undercurrents of urban culture, embodying the city’s beating heart and the whispers of its soul. I have often told my students that when they are out and about in their cities and hometowns, they should try to look a bit harder and try to read the city and the life within it. And in this case, explore urban art in its broadest sense: keeping their eyes wide open for the walls around us are not just barriers; they are canvases of conversation. They even invite us to take part in the conversation; An invitation that is maybe easier taken up when it is deeply connected to timely and urgent issues. In Berlin, for example, I came across an image that perfectly portrays this attitude of engagement: a wall that was originally branded with “no to vaccine” was updated with “yes to vaccine” followed by a small heart. This simple change demonstrates how these canvases reflect public feelings and the shifts they might undergo, inspiring us to engage in a discourse for the greater good.

The city speaks

The urban conversation could also speak about past and present struggles. Sociopolitical movements, civil rights struggles, and moments of cultural awakening have left indelible imprints on urban spaces. One poignant example that captures this essence is the housing struggle in the Netherlands. In a country known for its picturesque canals and tulip fields, housing has been a pressing concern for many. The sticker that reads “wonen is een recht,” (housing is a right), is a testament to this struggle. This unassuming sticker, which you might chance upon on a street pole, carries with it the collective voice of people demanding their basic right to housing.

As simple as it may appear, this sticker speaks volumes. It stands as a symbol of the resilience and determination of communities urging for a more inclusive and just housing policy. It’s a reminder that our spaces are not just physical structures but bearers of our shared human experiences and aspirations, beautifully visualised in yet another sticker saying, “Houses are for people, not for profit”.

The conversations that emerge through the ‘Imprints of Contestation’ are also a testimony to the different and diverse narratives that make up the city. In these urban areas, cultural traditions, subcultures, and marginalised voices find refuge and expression. The imprints serve as a canvas for reclaiming identities, questioning norms, and celebrating cultural diversity. One striking example that beautifully epitomises this celebration of diversity is an intervention I stumbled upon in Brussels. On a wooden construction fence, a simple tape has been affixed that reads, “I’m in love with an immigrant.”

This understated intervention breathes volumes. The phrase “I’m in love with an immigrant” interweaves the personal with the political. It is not just a proclamation of affection, but a potent reminder of the rich tapestry of cultures that intermingle in urban spaces. Through this declaration, the tape subtly combats xenophobia and challenges preconceived notions about immigrants. It’s a gentle yet powerful affirmation of embracing diversity, accepting the human experience in all its variegated forms, and recognising the integral role that immigrants play in shaping the soul of the city.

In this humble piece of tape lies a reflection of the conversations, connections, and shared narratives that truly embody the spirit of a city. It serves as a reminder that the ‘Imprints of Contestation’ are not just acts of defiance, but also profound expressions of love, acceptance, and the celebration of diversity.

The ‘Imprints of Contestation’ also serve as a remarkable conduit through which the city speaks, not only in defiant tones but also with a vision of hope and inclusivity. They weave a tapestry of alternative narratives that capture the aspirations of a society yearning for a more equitable and just world.

A prime example of such imprints includes those that paint visions of unity and social cohesion. Through vibrant colours and evocative imagery, they counteract divisive discourses by fostering a sense of community. They do not just criticise the status quo but dare to dream, showcasing the power of collective imagination in building bridges and nurturing mutual respect.

One instance of this I observed on a wall in London, which is further decorated with a plethora of street art, stickers, and paste-ups. Amongst the swirling sea of expressions, the heart, made from an array of colours and enclosing the word “hope,” is particularly striking. Adjacent to this beacon of optimism is another message that implores, “let your soul guide you.” This radiant duo exemplifies how ‘Imprints of Contestation’ can invoke positive sentiments. Hope is not a mere abstraction; it is the core, symbolised by the heart, from which individuals can draw strength. In addition, allowing one’s soul to lead suggests to me that wisdom and direction within us can guide us towards a more just and shared future.

The piece features a figure with a city map for a face, which could symbolise the deep bond between people and the cities they inhabit, or perhaps it portrays a figure wielding considerable influence in urban development. Beside him, there’s a rat clutching a key, possibly alluding to the critical decisions the city is about to make. Next to them, the message “cities for people, not for profit” serves as a bold statement against the commercialisation that too often consumes urban areas. The whole composition beckons us to re-envision our cities as more than just profit-making machines; instead, this imagery calls for reclaiming cities as living entities where human values take precedence over material gains.

Both examples exemplify the dual voices with which these imprints converse. While the piece from London whispers of hope and introspection, the Ljubljana street art raises its voice against the transactional nature of modern urbanisation. Each, in its own way, contributes to the tapestry of alternative narratives, bridging the divide between dissent and aspiration. Through vibrant colours and evocative messages, these imprints not only challenge but also inspire.

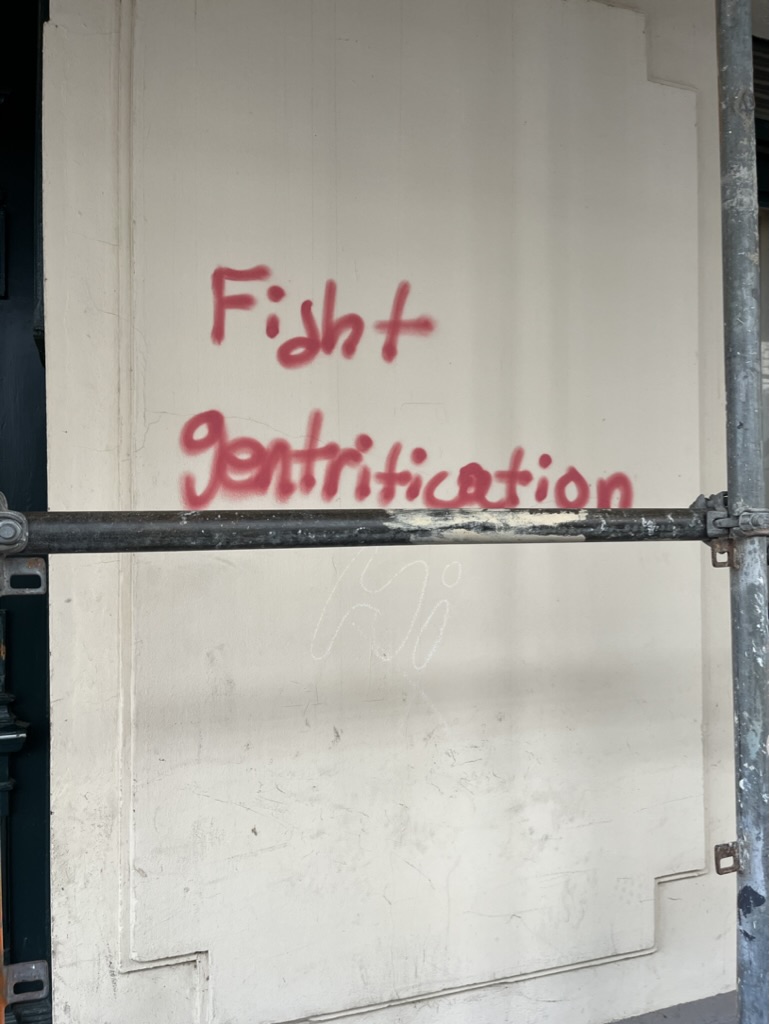

Yet, some imprints take on a more combative approach. Through stark visuals or straightforward language, they disrupt the complacency often accompanying dominant discourses. These imprints serve as unapologetic reminders of the pressing need to scrutinise and challenge the entrenched power structures that perpetuate inequality. Two examples, from Basel and Berlin illustrate the struggle against gentrification, each in their own tone.

The first image captures characters from the beloved Snoopy cartoon, taken in a neighbourhood in Basel, Switzerland, that is undergoing gentrification. They appear to be preparing themselves for a confrontation. One of the characters fiercely declares, “If you can’t smash it, burn it.” It is as if these familiar characters are lending their voices to the rallying cry against some apparently strong forces, I assume in this case gentrification.

The second picture is simpler but no less impactful. Taken in Berlin, it shows a wall with the spray-painted words “fight gentrification.” This graffiti symbolises the shared concern and unity between different cities in addressing the injustice of gentrification.

Although from different cities, these images are a powerful reminder that gentrification is not just a local issue but a global one. The fight for affordable housing and preserving cultural heritage and community diversity extends beyond borders. From Basel to Berlin, and across the world, the images show that communities are uniting to fight not just against gentrification but against the broader systemic injustices that often accompany it.

The text and images combined serve as a call to action. Gentrification often represents just one aspect of broader social inequalities and systemic issues that are deeply rooted in urban environments. While Snoopy and friends prepare to fight back in Basel, and activists in Berlin take to the streets, it is essential to recognise that the struggle is far from localised. It is a collective endeavour to build inclusive, equitable, and inclusive cities that reflect the diverse communities that call them home. The fight against gentrification is a fight for social justice and equal opportunities for all, and it requires global solidarity and action.

Whether through positive portrayals of an inclusive future or through confrontational challenges to prevailing norms, these different ‘Imprints of Contestation’ invite the city’s inhabitants to engage in a conversation. Through these tiny yet potent imprints, the city speaks; it invites its dwellers to partake in a dialogue that could lead to change, and that helps to reimagine the contours of their shared spaces and destinies.

Navigating the Thin Line between Rebellion and Spectacle

The political landscape acts as a crucible within which the ‘Imprints of Contestation’ either thrive or are suppressed. Urban spaces, in this regard, are not just physical territories but also political domains. They transform into battlegrounds where tensions of power imbalances, repressive policies, and systemic injustices simmer and sometimes erupt. These ‘Imprints of Contestation’ are not just works of art, but political acts that demand to be heard and acted upon.

In this spirit, an evocative paste-up from London, based on a Banksy work, portraying a defiant woman who appears to have just spray-painted the words, “If you want to achieve greatness, stop asking for permission,” enriches the narrative. This powerful image embodies the audacity and determination necessary to challenge authority and make a mark on society. Through her bold, unwavering stance, she symbolises the fearless spirit required to fight the complacency that perpetuates injustice and serves as an inspiration for individuals to take control and reshape the world around them.

Yet, as this wave of defiant creativity swells, the waters are clouded with unforeseen challenges.. The bold and audacious, as epitomised by the graffiti-laden figure from London, must be aware of a larger, predatory force at play. The compelling messages on the walls could find themselves swallowed by the very systems they strive to change, if not navigated with caution.

Stavrides (2017), leaning on Debord’s notion of the spectacle (1970), warns us that these anti-political expressions, such as ‘Imprints of Contestation’, run the risk of being absorbed by the spectacle itself. The spectacle, an assemblage of images that mediate social relationships, has the capacity to alienate and control. Consequently, there is an inherent tension; while ‘Imprints of Contestation’ aim to challenge and subvert, there is also the danger of them becoming part of the spectacle they aim to fight against (Stavrides, 2017). This warning becomes creepily tangible in Brick Lane, where street art that began as a radical form of expression is now often commodified as a trendy backdrop for social media posts, inadvertently making a subversive act part of the consumer culture it originally sought to challenge.

This insight by Stavrides is a call for vigilance. The ‘Imprints of Contestation’ are potent, but they must remain grounded in the communities and struggles they represent, and not be co-opted as mere images devoid of their revolutionary essence.

Musing and Discovering: The Journey Beyond ‘Imprints of Contestation’

When I developed the first ideas for this blog post, I was thrilled about sharing some pictures from my snapshot collection of ‘‘Imprints of Contestation’’. Diving into the literature on street art made me even more excited. But as I started putting my thoughts down, I realised there is much more to uncover. That’s something to look forward to – exploring deeper, linking these ideas with my other passions and projects. For instance, I see an interesting connection with our manifesto events. Just like manifestos voice the fight for a better future, these pieces of street art visually convey the same sentiment.

But that’s for another day. For now, I’ve decided to now and then share a picture of my collection on Instagram. I’d love for you to check it out whenever you can. Maybe an ‘Imprint of Contestation’ will remind you that we’re all in this together, fighting for a fairer city life. Or perhaps it’ll just brighten your day, or maybe it will challenge you to see the world through a different lens.

Caroline Newton is an urban planner, architect, and political scientist. She addresses the social and political dimensions of design.

Unless otherwise specified, all pictures are my own.

Related work that touches on some of the issues addressed in this blogpost can be found here:

The TU Delft Centre for the Just city

The Manifesto for the Just City: info on the website https://just-city.org/manifesto-for-the-just-city/. The books can be downloaded from https://books.open.tudelft.nl/home/catalog/series/manifesto-just-city . You can watch the videos on the YouTube channel of the Global Urban Lab.

Further Reading

Christensen, M., & Thor, T. (2017). The reciprocal city: Performing solidarity—Mediating space through street art and graffiti. International Communication Gazette, 79(6–7), 584–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048517727183

Dabène, O. (2020). Street Art and Democracy in Latin America. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26913-5

Debord, G. (1970). The Society of the Spectacle. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509200500536041

McAuliffe, C., & Iveson, K. (2011). Art and Crime (and Other Things Besides … ): Conceptualising Graffiti in the City: Conceptualising graffiti in the city. Geography Compass, 5(3), 128–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2011.00414.x

Ross, J. I. (Ed.). (2016). Routledge handbook of graffiti and street art. Routledge.

Stavrides, S. (2017). The December 2008 uprising’s stencil images in Athens. Writing or inventing traces of the future?”. In K. Avramidis & M. Tsilimpounidi, Graffiti and Street Art. Reading, Writing and Representing the City.Routledge.

Young, A. (2013). Street Art, Public City (0 ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203796917

Young, A. (2016). Street art world. Reaktion Books.